Dr. Guiseppe Foti, Superintendent, Antiquities, Calabria (right), supervises movement of the statues upon discovery in 1972.

Is it any wonder that after sampling the magnificent cities and incredible works of art of Rome and Venice that visitors to Italy rarely get beyond Naples? Well, yes, some do make it to Tuscany and Sorrento, but I like to get off the beaten path and that’s why I decided to take the train and head to the foot of the country, to Calabria. It’s a mountainous region with a questionable past and often overlooked by tourists. But here, off the rugged Calabrian coast, my travels were rewarded with a mystery that still intrigues archaeologists and historians.

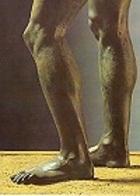

In l972 an amateur scuba-diver off the coast of Riace caught a glimpse of an arm protruding from the sandy bottom of the Ionian Sea. The Antiquities Department of Calabria was alerted and four days later, despite stormy seas, two enormous bronze statues were raised and carried to land. In the days that followed 2,000 years of marine incrustation was carefully cleaned away to reveal extraordinary workmanship.  While the statues had been cast in bronze, the eyes were a mixture of ivory and glass, the teeth were silver and the lips and nipples were copper. After micro-surgical instruments determined the inner structure and condition, technicians removed the lead tenons from their feet and emptied each statue of 60 kg of foundry earth, dust, clay, and sea sand. The dating of the soil convinced restorers that they were looking at original Greek statues of the 5th century BC and companion pieces of very few works surviving in the world today. Scholars now grappled with the questions. Who made the statues and what was their destination when presumably either shipwrecked in a storm or sunk in a battle? It is a mystery that captivated me from the first moment I entered the special room built to house the statues in the National Museum of Reggio Calabria. The anatomical detail is exquisite. I wondered if perhaps they had been destined for the great palace of Locri. The first statue has the features of a young man with a thick, curly beard. The second statue has lost its shield, lance and Attic helmet. He has a full, flowing beard and a more mature appearance. Restorers revealed that his right arm was not part of the original cast but soldered on at a later date.

While the statues had been cast in bronze, the eyes were a mixture of ivory and glass, the teeth were silver and the lips and nipples were copper. After micro-surgical instruments determined the inner structure and condition, technicians removed the lead tenons from their feet and emptied each statue of 60 kg of foundry earth, dust, clay, and sea sand. The dating of the soil convinced restorers that they were looking at original Greek statues of the 5th century BC and companion pieces of very few works surviving in the world today. Scholars now grappled with the questions. Who made the statues and what was their destination when presumably either shipwrecked in a storm or sunk in a battle? It is a mystery that captivated me from the first moment I entered the special room built to house the statues in the National Museum of Reggio Calabria. The anatomical detail is exquisite. I wondered if perhaps they had been destined for the great palace of Locri. The first statue has the features of a young man with a thick, curly beard. The second statue has lost its shield, lance and Attic helmet. He has a full, flowing beard and a more mature appearance. Restorers revealed that his right arm was not part of the original cast but soldered on at a later date.

Although recovered together the two statues may have been united only on the voyage and while they both represent the ideal warrior hero they are somewhat dissimilar in style. Scholars believe that the young man is the work of Phidias (460 BC) and the older man, that of Polyclitus (430BC).  Some theorize they may have come from a temple built by the Athenians to commemorate the victory over the Persians at Marathon; and others that they may be the work of Pythagorus who was the first sculptor to represent such anatomical details as veins and considered the greatest artist of Magna Graecia.

Some theorize they may have come from a temple built by the Athenians to commemorate the victory over the Persians at Marathon; and others that they may be the work of Pythagorus who was the first sculptor to represent such anatomical details as veins and considered the greatest artist of Magna Graecia.

Because of their weight (each weighs approximately 250 kg), whoever was transporting them would have had to use special equipment to remove them from their bases and load them onto a ship. The shields may well have been packed separately. It is unlikely that both statues could have been stolen in a quick furtive raid since many people would have had to be involved. Whoever removed them did it by force of arms or had approval. As for how they came to rest at the bottom of the sea, since there is no wreckage in the vicinity, the belief is that they were tossed overboard, either to lighten the ship’s load in a storm or to prevent them falling into the hands of pirates.

Owing to a number of missing elements, the Antiquities department authorized more underwater studies of the spot at which they were discovered. These excavations revealed a handle of one of the shields and the keel of a Roman Age ship and 29 rings of its sail rigging. But there was no evidence that the ship was connected to the Bronzes.  Today the statues are preserved in the Submarine Archaeological Section of the National Museum of Reggio Calabria where a special room has been fitted with gauges that measure temperature and humidity stability, and an aspiration unit for carbon dioxide and acids. To protect them against the motion of earthquakes, they stand on steel pins that rest on cushioned pistons inside cement pedestals. With all this scientific technology I couldn’t help wondering whether man will be as successful as the sea was, in protecting them for the next 2,000 years.

Today the statues are preserved in the Submarine Archaeological Section of the National Museum of Reggio Calabria where a special room has been fitted with gauges that measure temperature and humidity stability, and an aspiration unit for carbon dioxide and acids. To protect them against the motion of earthquakes, they stand on steel pins that rest on cushioned pistons inside cement pedestals. With all this scientific technology I couldn’t help wondering whether man will be as successful as the sea was, in protecting them for the next 2,000 years.

For more information visit http://www.italiantourism.com and http://www.turiscalabria.it and search under the Riace Bronzes or the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Magna Grecia in Reggio Calabria.